This interview was conducted following the national airing of 1913: Seeds of Conflict on PBS in the United States. 1913 is an hour-long, educational documentary based on the book 1913 Jerusalem by Amy Dockser Marcus. The film explores the social and cultural climate of Palestine during the waning years of the Ottoman Empire, and the experiences of both indigenous Palestinians and the earliest European Jewish settlers in the region at this pivotal moment in history. This interview engages a number of themes, including history and historiography, accessing and researching in archives, the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement, and the relevance of nationalism and national identities both historically and in the present day.

Eszter Zimanyi (EZ): Thank you so much for taking the time to do this interview; I really appreciate it! Ben, I was wondering if you could talk first about the inception of the film. I know a lot of your work has dealt with social justice issues and historical events, and I was wondering when you first decided to make a film about Israel-Palestine, and why you decided to focus on this moment in 1913?

Ben Loeterman (BL): Yes to social justice and my interest in that. I have not worked on anything [prior to this film] that I can think of immediately that focused on Israel or Palestine, so that was never particularly a focus of interest. However, I have a child who lives in Los Angeles and and a child who lives in Jerusalem, and they think very differently about the situation. I spend vacation time with them in Cape Cod every year, so that is the genesis of my long term interest. Once, when I was on my way to visit my daughter in Israel, I was getting on the plane and saying goodbye to someone. It was very embarrassing for me when he asked “What are you reading on the plane?” Now, I’m a filmmaker. I carry DVDs onto planes, I don’t carry books, so I wasn’t reading anything. He gave me this thin little book called 1913 Jerusalem, and he said “1913, that’s your year,” because I made another film specifically about events in America in 1913 [The People vs. Leo Frank] and a couple of other films from around the turn of the century. So, I took it and it turned out to be the book by Amy Dockser Marcus. Once I read her book, I became very interested. She referred, in her book, to a feature length documentary film from 1913: Noah Sokolovsky’s The Life of Jews in Palestine. To me this was a gift, and I thought it was worth making a film about.

EZ: Getting into this idea of framing your film around another film, I thought that 1913: Seeds of Conflict really raised so many interesting questions about not only about how the occupation and colonization of Palestine has evolved and unfolded, but also about how history is constructed. Your use of archival material and the way in which your film, I think, is very reflexive about being a construction itself, was very interesting to me. I was wondering if you could speak a bit more about your research process after you read Amy’s book, and if you knew immediately that you wanted to frame your film around Noah Sokolovsky’s. How did that process evolve?

BL: I’m always interested in history as a perception, as opposed to a set of facts. I really do believe that how we understand history is based very much on where we are looking from, as much as what we are looking at. So for me this whole question of thinking about what is happening in the region today, [was tied to] looking back 100 years and trying to find that kind of resonance or meaning in it. Particularly for me, I’m a west coast Reform Jewish-American. What do I know about Ottoman history, and what interest would I have in it? But as we dug in, and found that people are actually doing new scholarship in this area, it piqued my curiosity to learn more and to pursue this idea of perception. Sokolovsky’s film is exactly the mythology that I grew up with and learned as a child. So it was very interesting to peek beyond the edges of the film and see what else is going on.

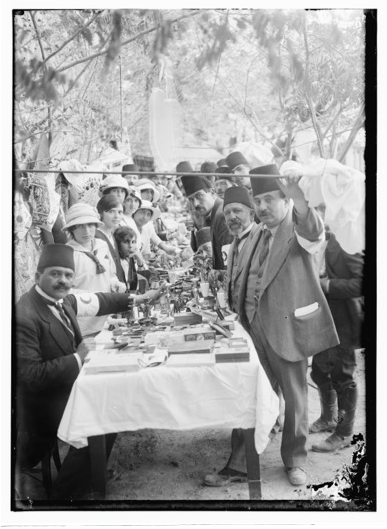

EZ: I loved that moment in the opening of your film when, as we’re watching Sokolovsky’s work, the reel is paused and a voice from off camera asks “Who’s that at the top of the frame?” In that moment, we see that there are indigenous Palestinians in the background observing the newly arriving Jewish settlers from Russia. In a later scene, Dr. Michelle Campos points out that the position of the camera and the framing of the image can create deceptive representations, a kind of “selective reality.” Both these scenes reminded me of Edward Said’s famous statement that, “the whole history of Palestinian struggle has to do with the desire to be visible,” and I really appreciate the way this question of subjectivity undergirds your film. 1913 seems to ask us to think about who gets to tell history, and how. Can you speak about the systematic way in which the Zionist narrative has sought to minimize or erase Palestinian claims to existence, and the importance of film, photography, and other media in combatting or propagating this erasure?

Elisha Baskin (EB): From doing research on these topics and about the history of Palestine, it seems like most of the primary resources are in Israel and in Israeli archives. That greatly impacts the possibility for Palestinians to write their own history if they can’t access the primary sources. A lot of the sources for 1913 came from the Ottoman archives in Turkey, but that is also related to your question, because the historians that were writing about this early Palestinian conflict, up until probably the 1980s, were looking at it from a British imperial point of view. They were studying European languages and working with the British archives. The people interviewed in the film are of the first generation of scholars to study Turkish and look in the Ottoman archives, which has completely changed the historical narrative and that shed new light on the historical events.

EZ: I’m curious about your experience with accessing these archives. Did you have any difficulty accessing documents?

EB: It’s important to emphasize that we didn’t do the majority of the primary research. We used material already studied by the scholars who appear in the film. They’re the one’s that did the real research. We just re-used what they already found, studied, and analyzed. Nevertheless, we did go to archives to find copies of the main documents and photographs. Doing that is not always so easy here in Israel. First, because the system is not user friendly for the most part, but also because there is constant fear and suspicion in the archives in Israel. We would get questions like, “why are you here, what is your film trying to say, what side are you taking?” Sometimes documents are not where they are supposed to be. I guess that happens everywhere, but the politics are always present and the fear of whose side are you on will probably determine the level of cooperation you get from these institutions and archivists. And I’m an Israeli Jew, so you can imagine what the attitude would be towards anybody who is not an Israeli Jew and is trying to access these documents about early Zionist history in general and land related documents in particular.

BL: I think, as an Israeli Jew and a native Hebrew speaker, Elisha may have come across some of that nuance of perception or reaction to our questions in archives that I would have no idea about. What I found was two things: This history is not user-friendly. It is very exciting, because no one has really looked at it, partly because nobody in the archive world makes it easy to look at. This is difficult stuff to dig out. You need a lot of good equipment and different sized flashlights and screwdrivers to pry it out of wherever you’re trying to [get it out of]. Number two, there is a feeling one gets, as one is taking one’s little pickax like you’re looking for some sort of Jurassic Park dinosaur bone or something, that makes you say, “Wait. There is a vault. There are museums. There are grand rooms full of history from one side, and very little from the other.” There were times when we were looking for passages from Arabic newspapers, and we could only find them in Hebrew newspapers, which had quoted those Arabic newspapers at length. We tried to create the illusion, which was a license I took as a filmmaker, to make you think you were looking at the original Arabic newspapers [in the film]. They just don’t exist. So from the standpoint of somebody who does this research, and likes the challenge of finding these original sources, it’s kind of tragic and very sad that there is a lot that exists from one standpoint and little-to-none that exists on the other. So that was both a challenge and a difficulty.

There was one moment I had, where there was an essay I was trying to find entitled “The Ottoman Revolution and Young Turkey.” It was published in two Cairene - that is to say Cairo - journals by Ruhi Khalidi. Michelle Campos’ footnote [in her book] says, “a manuscript version, dated October 20th, 1908, is preserved in the Jewish National and University Library.” I can’t tell you, Eszter, the number of days I went to the Jewish National and University Library trying to find this document, this essay by Ruhi Khalidi. And then I had Elisha go. And then they confirmed to us over and over and over again that they had never heard of this document and they have no copy of this document. They looked at [Campos’] footnote and they said “I’m sorry, we can’t help you.” At this point, I got scared, because I’m a journalist as well as a filmmaker. I wondered if Michelle Campos was not being totally truthful with us. Did this document exist? So I got on a plane and went to Florida, and I met with Michelle Campos. And she said “sure I have [the document], here’s my copy.” And she hands me a copy to Xerox - every page of which is stamped “The Jewish National and University Library.” So it’s disheartening to think that some of this history is either lost, or for reasons that I can’t explain, is being hidden. I think that’s a shame.

The last thing I should emphasize that Elisha said, and I should have said earlier, is that our job and the funding we received was to showcase new scholarship going on. So the credit really goes to the scholars, many of whom were interviewed in our program. People like Yuval Ben-Bassat and Michelle Campos and Abigail Jacobson, who have trekked to the Ottoman archives. Or in the case of Gur Alroey some easier archives, archives that are to be found in Rehovot, that nobody has particularly bothered to look at.

EZ: That’s an incredible story. I think there is definitely a sense, in academia as well as the general public, of an immense fear and tension that exists whenever someone brings up this topic of Palestine. It does seem like it becomes increasingly difficult to access archival material when doing research on this particular subject. It also seems to be difficult, at times, to convince people to speak publicly about Israel-Palestine in a critical way. That said, can you speak more about how you selected the scholars interviewed for the film? I noticed that the majority of your interview subjects seem to be scholars of Ottoman or Zionist history; and while Palestinian voices are well represented through archival material (diaries, essays, letters, etc.) only three of the scholars interviewed in the film are Palestinian. Was this due to availability or were you attempting to speak to a specific audience?

EB: There aren’t that many people out there who have written about this history or who relate in their scholarship to the characters that surface in Seeds. The story is not just an overview narrative of a historical period. It’s focusing on people that lived during that time, and people whose words were made available to us by scholars. So our focus was to find scholars who have read these original documents and have written and published work about these people. I think that was the main motivation for choosing people. It wasn’t like, “we need Jews to talk to a Jewish American audience.” Quite the opposite. It was very important for us to have a variety of voices, identities and perspectives in the film. Also, there was a great deal of pushback with some of the Palestinian scholars, some who did not agree to participate in the film, and even with those that did participate. It wasn’t smooth the entire time.

BL: I would energetically refute any notion that there is any question that the people we ended up speaking to, or didn’t end up speaking to, was due to their availability. We decided who we wanted to speak to and we dragged them wherever we had to in order to speak to them. We spoke to exactly the scholars we wanted to speak with. There was one Palestinian scholar, Adel Mana, who we wanted to interview and who would not speak with us. Having said that, we are very proud of the Palestinian scholars we have in the film. There is no question that we spoke to who we spoke to because of their scholarship and what they study. In addition, I would think of many of these scholars as speaking to a Palestinian point-of-view, even if they are not themselves Palestinian. And I cannot tell you how rewarding it is as a filmmaker, and it’s really an honor, to see that Salim Tamari, Beshara Doumani, and Issam Nassar have tremendous respect for the finished product. That said, during our research, I questioned why there are not more Palestinian scholars, or scholars of Palestinian heritage, doing research on the Ottoman period in Palestine. If there were, we would have found them. It’s an interesting question, but also maybe an obvious one. If we’ve talked to you about the fact that there are vaults full of scholarship of one kind, and a tiny little folder of scholarship of another kind, maybe scholars aren’t going to be so drawn to those archives. It’s a real problem of historiography, and how we tell history and from what vantage point.

EB: I want to add one little point, which is that there are no certified PhD programs in the humanities in any of the Palestinian universities in the West Bank or Gaza, as far as I know. It’s true that many Palestinians study abroad, but not having access to PhD programs locally impacts the volume of research done on these topics from a Palestinian point-of-view, and the ability to lean on local sources.

EZ: There does seem to be a big question around access to institutions in Israel-Palestine itself, especially for Palestinians who are living there and who want to do work on Palestinian history and culture. I imagine it is difficult for Palestinians in Israel-Palestine to conduct any kind of research that is political in nature, and that might challenge the general public’s understanding of Israel-Palestine’s history.

BL: I’m curious to know whether Elisha would agree with that or feel, as I tend to do, that there’s not the source material there to dig through.

EB: I think that there probably is more material to dig through, and most of the written material is in Israel for two main reasons. First, destruction has taken place over the years to the Palestinian locations where resources have been housed, whether through war or through the Israeli Army looting stocks of entire archives—as is the case of Abandoned Property books in the National Library—or destroying them / making them disappear, as with the PLO [Palestinian Liberation Organization] archive from Beirut. Second is that the Zionist movement documented its work meticulously and its culture was based on a written tradition rather than an oral tradition. So it’s true that Zionist history is much better documented and has survived, however, I think there is still a lot to look for. Access remains a big obstacle. There are students who are unable to go through the archives because of restrictions on movement, lack of permits, language barriers and suspicion in the archives. So I don’t think there’s not material to go through but there is definitely a gap in the amount of written primary sources available on Palestine. On the other hand, as Beshara Doumani says in an interview we did with him on Palestinian historiography, it all depends on what questions you ask and what sources you consider. Sources are not preconfigured. Some historical sources are gaining more credibility in academia, including the use oral history and photography.

BL: I would say, on one hand that makes it very exciting I think, to think that there’s a whole new realm of resources on Israel from the Ottoman archives that can illuminate this history. I think it’s an exciting idea to think of more scholars of every stripe and religion and nationality, and especially scholars from Palestine, going and looking through more of this and unearthing new information. I would also say, separately, I think Elisha’s right [about the way these histories have been documented]. Whatever material there is in Arabic has been translated to a much lesser degree into English. So whenever that happens, communication becomes a barrier for study.

EZ: I’d like to turn more towards the perception of the Israel-Palestine “conflict” itself. Often times, we hear the cause of the Israel-Palestine “conflict” reduced to a “centuries old” hatred between Muslims and Jews. This narrative, to me, suggests that the violence in Israel-Palestine is inevitable. However, your film seems to point to different underlying causes of the occupation. Can you speak more about what your research has led you to believe are the root causes of the Israel-Palestine conflict and why (or whether) you feel the “Jews vs. Muslims” narrative is misleading or unproductive?

BL: I think Elisha and I should answer this separately, because as an American Jew, what I learned was not that this was a centuries old conflict, but that as Jews emigrated from Eastern Europe, especially to the region we call Palestine, we built a homeland for ourselves that eventually led to statehood. And we don’t really learn how that happened. We sort of learn that it happened like mushrooms: there was one mushroom that came and then another mushroom bloomed and pretty soon there was a homeland, and that’s a wonderful thing. What we American Jews don’t learn is details of how that happened, and the strategic planning that was needed to pull that off, and sometimes the very strategic planning for a life that was going on in that place.

EB: I had the same upbringing even though I studied in the Israeli school system my entire life. We learned about the conquest of land and the conquest of labor but never in the context of there being another people here. So we did learn about the steps and the strategies and the project and everything it entailed, but never in relation to another group or that there were any kind of conflicting national aspirations at this point in time. I think another thing that’s very ingrained in people is [the idea] that national sentiment is something that happened a lot later. That there was Zionism and there was no reaction to it, and only later, during the British Mandate, did the local population of Palestinians start to see themselves as a national group. And in the film you hear from people like [Khalil] al-Sakakini who, already during this Ottoman period, were talking about national sentiment and the relationship between the land and the community. Many journalists at the time were also standing up for the agrarian class and trying to move people into action against the sales of land to the Zionists. But none of this was something I learned about growing up in Israel.

EZ: I’m wondering if there was a shift in your understanding of this narrative as you made the film, or if you had already learned this information before making 1913? What do you now believe the root causes of this conflict are?

BL: What I learned, and what I’ve been heartened to learn, is that this is not an ages old conflict. This doesn’t go back to Biblical times, because from the research and the scholars we read, it seems as though until the late 1800s, there was a long period when Jews and Christians and Muslims lived together and coexisted and did so harmoniously, and mostly peacefully. This is not to make a Garden of Eden out of it, but there was peaceful coexistence until the late 1800s. That was with Christians and Jews understanding that they had a second-class status in what was then an Islamic empire. So it’s not to say that Jews and Christians and Muslims lived exactly equally, just that they lived together harmoniously. That’s what the scenes about the coffee house life are meant to portray in the film. It’s a nostalgic thing, and to many people like myself, a warm-hearted idea. It’s reassuring to think it wasn’t always divided up, it wasn’t always the Arabic quarter and Jewish quarter, there was a time before all that nonsense. It makes one rethink one’s values about what is happening today and why.

EZ: Elisha, you touched a little bit earlier on this idea of nationalism, and that there’s an idea of nationalism in Israel developing after Zionism. I thought that your film explores this concept of nationalism in a really interesting way; in a sense, it seemed to me to point to this concept as one that is potentially dangerous and conducive to escalations of violence. There is a way in which the rise of nationalism is pointed to as a partial cause of increasing anti-Semitism in Europe in the early 1900s, the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, as well as rising tensions between newly immigrated Ashkenazi Jews in Palestine and the indigenous Arab-Palestinian population. At the same time, people might argue that a sense of nationalism has been a vital component in preserving specific histories, cultures, identities, and for Palestinians, a claim to existence within the present-day occupation. How do you see this idea of nationalism functioning over time, as well as in the present? Do you think, in today’s globalized world, that we might need to imagine something other than the nation-state as a model to live within?

EB: I don’t think I have much to say in the context of our film, except that Israeli nationalism and Palestinian nationalism today in 2015 are not the same or equal. There is a state called Israel, and there is no state called Palestine.

BL: The film certainly takes note of the phenomenon of nationalism, which is really sweeping the world as the system of empires gave way toward the turn of the 20th century. This is happening in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, this is happening in the Russian empire, in the Ottoman Empire and elsewhere. Now, I’m not a political scientist at all, and I would be wrong to voice ideas without a stronger foundation than I have, but I do think that today we are questioning in different parts of the world whether the idea of nation-states, which have sustained the world largely for a century now, are in certain places not fulfilling the goals and the needs of the people who created nation-states a century ago. I think in vast parts of the world [nation-states] do [fulfill these goals]. But I think when you look at certain areas, where there has been, forgive the term, a Balkanization, whether that’s been in the Balkans, or Syria, or Iraq, where you have people like the Kurds asking about their nation-state, or Palestinians asking for their nation-state - whether there is or will have to be a different model, I don’t know what that is. I don’t know if it’s a confederation, or a one-state solution versus two, or three, or five, but I think it’s an interesting moment in history to recall how nation-states came about, and to help us think about looking forward. Are there different ways for people to live together?

EB: I would also add that in the film we are showing people who were foreseeing the direction that this conflict was heading in as early as 1913 from within the Zionist movement. They tried to warn against the consequences of creating a separate and secluded society within Palestine. This is especially true of Ottoman Jews who were born in the Middle East and spoke Arabic, people who had ties and relationships with the Muslim and Christian population and wanted to maintain a multi-cultural society and rejected the exclusivist Zionist model promoted by some of its leaders.

BL: That’s to say that someone like Albert Antebi, who is a single character who in our film represents a wider spectrum of voices from Sephardic or indigenous Jewish population living in Ottoman Palestine, worried about the potential dangers of nation-states. So it’s not to say that our film is trying to take a particular view that is pro-nation-state or anti-nation-state, just that we are trying to, I hope, look through a slightly more nuanced lens.

EZ: The inclusion of documents written by people like Antebi, who were skeptical about some of Zionism’s aims from the start, is in my opinion one of the most significant aspects of your film, and brings me to my next question. How important is it for Jews in the diaspora, who maybe do not have any direct experience with Israel-Palestine, to understand the difference between political Zionism and Judaism? I’ve found, from my past experiences as an undergraduate student in California, that there has been – and continues to be – significant efforts to limit pro-Palestinian student organizing across college campuses, and in particular, to prevent the growth of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) campaign. Often times, these anti-BDS campaigns suggest that critiques against the state of Israel are by nature anti-Semitic. I’m curious about your opinions on the conflation that seems to happen between the Jewish identity and a politically Zionist identity, and whether it was an intention of your film to unearth the differences between those two identities?

EB: What you’re speaking about is a real problem – and sadly it’s not just the anti-BDS leaders who conflate criticism of Israel with Anti-Semitism, it’s something that has also occurred within the BDS movement occasionally. I think it’s very important for everyone involved to separate Judaism and Zionism – they are not the same thing. This topic is indeed extremely polarizing and it’s interesting to see how its becoming a louder and more prominent conversation within communities or student groups. Part of the brilliance of the call for BDS is that it really changed the conversation, and now people have to re-align their positions in relation to this growing movement.

BL: Your question was about understanding the difference between political Zionism and Judaism. I think the answer is it’s very important. And I think that’s because Jews worldwide are extremely sensitive, and have reason to be from their history, of a conflation of concepts like anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism. This is an area where precise, and loud communication helps. That is to say, where anti-Zionist views are expressed, then the louder they become expressed, there should also be a separation and a clarifying voice that explains that this anti-Zionism should not be confused with anti-Semitism. Equally, I think on the reverse side that students on college campuses who have a pro-Palestinian vantage should find ways, and be able to find ways, to express their concerns about political Zionism through addressing issues like BDS without necessarily being accused of attacking Jews or attacking Israel. I grew up in Los Angeles as a very assimilated Jew. We were taught as little kids that Israel is our homeland and we should support it, spiritually, with money, with tzedakah, or charity, so you know, speaking only for American Jews, we mix that pot up a lot. It’s very hard to separate these things, but very important. I would say that certainly the politicization of issues about people being able, or finding ways, or needing to find ways to live together, and the polarization of those issues to the point where there are things happening, like you’re talking about, on American campuses, whether it be “anti-Israel” being confused with “anti-Jewish” or those things being confused with the BDS movement, or in some cases vice versa, pro-Palestine movements and students either being silenced or singled out because of that, in a discriminatory or demonizing way, is saddening. It’s not heartening. That’s why we feel like part of our film is to hearken back to a time when that didn’t seem to be the way people were treating each other; it’s both nostalgic and worth hearkening back to.

EZ: What has the reception for 1913 been like since its premiere on PBS and what do you hope the film will inspire people to do, if anything?

BL: I think in terms of stark numbers, we couldn’t be and shouldn’t be more pleased with the results of the broadcast, and events leading up to the broadcast. We’ve just received ratings back, more than a million and three quarters people saw this film. Those numbers are big by any stretch. During the week the film aired, the film received higher ratings than some regular PBS series like Frontline or NOVA. And we had some wonderful successes, such as stations like the New York PBS station adding an additional half hour program to discuss the issue. So those are things to be very heartened by. The film got a tremendous amount of exposure and we shouldn’t dwell on the negative.

However, as productive and stubborn people we will for a moment, and say that it is very disheartening, that although PBS stations across this country far and wide, large and small, aired the film, and overwhelmingly did so in the time frame that PBS programmed it nationally, there are also what for us are setbacks. Which is the fact that the Miami station decided not to air the program in a place where the sixth largest preponderance of Jews in the world exists. We can’t tell you why that happened, we can just tell you we’re saddened that it happened. We can tell you that certain people have said there are large Jewish philanthropic interests in South Florida that were not unhappy to see the program not air there.

A film like this is far and foremost, we hope, an educational tool. To that extent, and to the extent that the DVD sells and people are streaming the film far and wide on the PBS website, we are very heartened. And that we continue to be asked to screen it in places as prestigious as Yale, and as different from Yale as the Rhode Island School of Design, is also a very heartening thing. We are not heartened by the fact, and do not rest from the fact, that we have not been successful in finding partners within educational organizations to help develop curriculums, teachers’ guides, and discussion guides for the film. We have not found that in the Jewish world, which does this a lot and did so for another film I made about anti-Semitism in 1913. So that’s particularly disheartening. And we ourselves wonder whether, if a Palestine-oriented organization raised their hand to do so, first of all we’d be thankful and would work and partner with them, but would wonder how far and wide those materials would be used. That is to say, what the film has a goal, and what action we hope people will take, is for people to discuss and to learn. I don’t think it’s a call to activism. I think there are differences on a spectrum where you can say, does a film like Five Broken Cameras or The Gatekeepers call for activism or not. Our film was really funded by the National Educational Endowment of this country to help Americans understand what is happening in different parts of the world. I think that’s what I want people to take from it and do with it. And to the extent that those are Jewish people, to really understand and face our own history. Because that’s partly who I am, and that goes into the filmmaking, there’s no denying it.

EZ: Has the film screened in Israel-Palestine or will it screen there?

EB: Eventually, I hope so.

BL: The film can also be streamed on the PBS website for free until 2024.

EZ: Are there any other resources you would like to point people towards if they’d like to learn more about this issue?

BL: Yes! We definitely suggest and encourage people to go to our website, http://www.1913seedsofconflict.com . We put a lot of energy into the website as a way of footnoting our film, which is a hard thing to do. There are good resources on there, as well as an hour long video conversation between Salim Tamari, Beshara Doumani, and Issam Nassar about specifically Palestinian historiography. I honestly, seriously, encourage people to go there and view that conversation. We also encourage people to feel free to contact us if they would like to.

EB: We have several resources on the website including a discussion board, information on the historical characters featured in the film and the list of archives we used.